Written by Nate Drolet

As you become more advanced in climbing, one of the most important skills to cultivate is the ability to interpret feedback that climbs give you. When you fall off of a boulder, can you answer, “What happened?”. Difficulty can show up in many shapes and forms, and the better you get at recognizing them, the better you’ll be at overcoming them.

Whether you’re trying to stick a move for the first time, make a move feel more efficient, or are searching for better beta, you have to work to understand the relationship between yourself and the moves. The better you can decipher these messages, the faster you’ll be able to direct yourself toward better solutions, and the harder you’ll be able to climb.

Below, I’ve grouped together what I believe are the eight primary obstacles we face every time we climb. I’ve done my best to explain:

- How to identify each obstacle in your climbing

- How to train for each obstacle

- Common mistakes you might make with each obstacle

- Common themes you should be looking for within these obstacles

- How to use obstacles to your advantage if you find that it’s a strength of yours

Things to consider while reading:

- Don't get overwhelmed: The goal of this article isn’t to leave you overwhelmed with a dozen new things to worry about with your climbing. Try to read this with an open mind and look for one new takeaway that you can apply immediately. If you find a point that resonates with your climbing experience more than everything else, take that and run with it!

- Assess why problems feel hard in the moment: The points in this article will allow you to better ask, “Why am I regularly falling, and what can I do about it?” Step one will be to appreciate that as climbs get harder, so do all of the obstacles. We’ll never be able to train or prepare so much that holds never feel small or moves never feel big again. If all the holds feel good to you, you either aren’t trying hard enough climbs or you are being held back so much by other items on the list that you aren’t getting a chance to fully challenge your hand strength.

- Reframe climbing difficulty: Once you accept that obstacles are permanent parts of climbing, you can go from despising them to using them as a tool for improvement.

- Identify: Does the difficulty dictate your decision-making when choosing climbs? When you look at problems and decide if they look good or bad, or if they seem to suit you, what about these climbs signals this to you? While this list isn't all-encompassing, if you can see a pattern among climbs you want to spend the most time on or those you skip most often, it might help you uncover some underlying strengths and weaknesses in your climbing that you weren't aware of before.

- Ask yourself: Are you training to be a one-trick pony? The goal here isn’t to take all the joy and intuitive exploration out of your climbing by over-systematizing. This article aims to bring a little more awareness to what’s happening right in front of you, so that you can keep progressing year after year rather than feeling stuck and not understanding why. As previously stated, difficulty can come in many shapes and forms. The more forms you are aware of, the better you’ll be at addressing your weaknesses and leveraging your strengths.

- Know this: Knowing about a problem is not enough. For experienced climbers many of the points discussed below may feel familiar if not obvious. These concepts are intuitive once you pause to think about them. However, as you read through this, it’s important to remember that having a deep understanding of the basic principles relies not only on the knowledge that they exist but the action taken to incorporate them into your problem-solving process.

Regardless of how self-evident an idea might seem, what truly matters is putting it into practice. Common sense isn’t always common practice. If something seems basic to you, pause and ask yourself if this is something you embody with your climbing or is it just something that you know you “should” do.

Truth 1: “The Holds are Bad”

This one: Our Sisyphean task. We encounter a climb or a grade where all the holds feel awful. We work hard to make our fingers stronger and find brief success at our current level only to try the next grade and realize that the holds feel terrible again.

This is probably the easiest of the obstacles to identify. If a hold subjectively feels bad to you then it’s a bad hold. One person’s “jug” is another person’s nightmare.

Are there specific hold types that feel worse to you? Consider this: Hold size might not be as big of a deal as you think. Some people can crush small flat holds but struggle with small incuts. Finger strength is fairly hold-type dependent, so it’s worth tracking which types give you the most trouble.

Once you have determined (at least on the surface): “this hold is bad,” and which hold(s) are giving you grief, follow up with these questions: “Is this actually a finger strength problem?” and "Can you statically hold the holds comfortably, but you have trouble moving between them?" The “bad hold” might be more of a positioning, footwork, coordination, or power issue.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the hold types that give you the most trouble, you can get down to brass tacks:

- Project hard holds: First, warm up properly until you are ready to try hard. Then, spend the freshest part of your session trying very simple climbs, with small, non-complex moves on bad holds. If fixing a weakness, such as crimp strength, is a priority for you, work on it during the part of your session where you feel the strongest.

- Practice repeats: Yes, our body gets stronger from high-intensity workouts, but it also needs an appropriate amount of volume for optimal results. Repeats, therefore, are essential. My biggest recommendation? Create a list of problems to repeat. Create the list from the newest set at your gym, so that it doesn’t get reset quickly or, for an even better long-term approach, use a wall or board that doesn’t change, so that you can continue to repeat problems for months or even years. This will allow you to add more variety to your “bad holds” approach and track your progress with this weakness over time.

If Bad Holds Aren't Your Weakness

Is using bad holds a strength of yours? Congratulations! Must be nice. In all seriousness, if you find that you rarely encounter holds that feel bad to you and it’s always other issues that are slowing you down, I have three recommendations for you:

- Work hard to improve other aspects of climbing: Feeling competent on hand holds is such a boon for improving at climbing. The more you can level-up your other skills, the better you’ll be able to leverage your superpower, and the more well-rounded for climbing you will be.

- Continue improving your finger strength: Just because you’re good at something doesn’t mean you can’t get better. While you’re shoring up your other weaknesses, keep a little bit of simple climbing on bad holds in your regular rotation.

- Supplemental training: There are many great ways to improve your finger strength off the wall. While the work you do on the wall will have the greatest direct carryover to performance, it can still be valuable to add a little extra work on top of that. If that’s something that interests you, you can check out Tension's article, Hangboarding: A Way.

Truth 2: You Need to Cultivate Self-Belief to Climb Stronger

What most of us want is stronger hands. What most of us need is greater belief. I have self-belief as second on the list because it’s one of the most important attributes you can cultivate in climbing. Having belief in yourself has an impact on your climbing every time you pull off the ground. It’s hard to stick moves that you don’t believe you can do.

We’ve all experienced that moment when we finally get close to sticking a move and have a mental shift about it. It’s at that moment, we realize we didn’t actually believe we could do the move until right now. Once you’ve gone past that tipping point, actually doing the move becomes a matter of “when” and not “if."

Self Doubt as a Limiting Factor

To cultivate belief, you have to address the possibility that you may be crushing yourself with self-doubt. If you’re trying to identify whether or not belief is a self-limiting factor, the two best places to look are self-talk and how you act when moves feel hard.

When something feels nearly impossible (which is a near-daily occurrence when you’re pushing yourself in climbing), how do you respond? Do you drop off multiple times before fully committing to a move? Do you use language that helps with your problem solving, such as, “I need to find a way to get more weight on my feet and off of that left hand," or do you use language that is defeatist, like, “I just can’t hold that hold?”

Belief is the foundation upon which every other climbing skill is built. No matter how strong your fingers or how powerful your body, if you climb with hesitation and back away from challenges at the first sign of difficulty, your climbing progression will be hindered.

Struggling with belief isn’t all bad, though. If you can pay attention to it, you can use moments of doubt as tools to identify where other problems are at play. When you find yourself expressing doubt about a move or a problem, can you pinpoint what it is that’s causing it? Is this a regular occurrence? The more tapped into your inner dialogue you can become, the faster you can recognize weaknesses.

Don't Co-Sign Your Own BS

Perhaps the biggest enemy of believing in your abilities is the idea of "being logical." Climbers who struggle most with self-doubt are often the most skilled at disguising their weaknesses as simple facts of the universe. If asked why they haven't tried a certain beta, they might respond, "I know I can't do that. And that's not me being negative or pessimistic; I just know my body and what I can and can't do."

The great thing about convincing yourself that you can't do something is that you'll never be wrong! Pay attention to how you talk about difficult situations, and try to catch yourself if you start becoming defensive or intellectualizing your weaknesses as irrefutable facts.

Concrete Practices for Belief Cultivation and Climbing Harder

There are countless ways to improve your beliefs and combat your doubts to succeed in climbing. If you find a method that works best for you, stick with it and see it through for as long as you can! And if you don’t currently have a system for developing belief, here are concrete methods I recommend:

The 7-Go Rule

For climbers who want to improve their belief in their ability to do harder moves, this is the place to start. For many, this rule alone will make an enormous impact on their belief and, consequently, on their ability to climb harder.

Most people don’t realize how fast they move on from a climb that feels hard. This is especially true for more experienced climbers, who have convinced themselves that they know what they can and “can’t” do.

Whenever you encounter a move that feels so hard that you want to move on from it, try it seven times before you pass any judgment as to whether it’s too hard or not. If, after seven tries you make any progress, even if you only went from barely pulling onto the wall, to being able to hang on for a few seconds before falling—keep trying it. You can choose to keep trying it in the current session, or plan to return in the future. If you make absolutely zero progress after seven attempts, you have permission to move on.

Why seven? It turns out seven tries is a decent sweet spot for most people to be able to see enough progress on an “impossible” move to convince them to keep going. If you only take one thing away from this entire belief section, take the 7-Go Rule.

Pyramid Building

Another concrete way to cultivate belief is a climbing pyramid. Few things build confidence as well as regularly sending fairly challenging climbs through pyramid building. Being able to pull onto the wall with the belief that you’re going to the top is a skill, and if you don’t practice it somewhat regularly, that skill atrophies.

Benchmark Climbs

Not to be confused with Moon Board benchmarks. Benchmark climbs are problems that you can return to over months and years as a check-in to objectively track your progress. While outdoor climbs work well for this if your goal is climbing harder outdoors, inconsistent conditions and access to these climbs can make it hard to reliably use them as a measuring stick for progress. Indoor problems that don’t change have their own drawbacks, but seem to be the best tool we currently have.

To see a great example of benchmark climbs, check out this video of Will Anglin’s V8B circuit.

Reframe Difficulty

Remind yourself that hard things are hard. As silly as this sounds, it’s easy to become discouraged by hard climbing. If you put a lot of effort into your training and preparation, only for your project to still feel incredibly challenging, it can be disheartening. That’s why it’s important to remember that hard climbs will always feel hard. Remind yourself: We pursue these climbs because they are challenging. If it was easy, you would just do it and move on. Your goal with training shouldn’t be to make everything feel easy; it should be to see what’s possible and stretch yourself to the limits of what you’re capable of.

Truth 3: Sometimes the Moves Feel Too Big

If and when the moves feel too big, you’re not alone. This is probably the second most common obstacle that people encounter in climbing, right after “the holds feel bad.” Many people describe hard climbing as big moves between bad holds. While this is obviously an oversimplification, there’s plenty of truth to it.

One thing that’s unique to big moves is that it’s the most quantifiable obstacle in climbing. For that reason, I think that this is a great starting point for people who want to learn how to spot patterns in their climbing weaknesses.

Common themes to look for when struggling with big moves:

- Do big moves feel harder when they are vertical reaches or horizontal?

- Do you only hesitate with big moves when you’re high off the ground? (this might be more about belief than the big move itself)

- Does it feel harder to get enough distance to reach the next hold or to arrive at it with enough control to latch it?

- Are there foot or body positions that feel hardest for you to do big moves from?

- If you can match on the hold you are on before doing a big move, is that significantly easier than doing a big pull through from offset holds?

- Are there any things that feel like they nullify big moves for you? These could be heel hooks, high feet, low feet, keeping your feet on, underclings, etc

Once you pause to think about it, there are a lot of unique types of big moves. The more you can narrow down what exactly it is that makes a move feel big, the better you’ll be at addressing that weakness.

How to Approach and Send a Climb When the Moves Feel Too Big

Big moves can be one of the most intimidating aspects of climbing, especially when they feel just out of reach. Rather than immediately assuming a move is impossible for you, it's important to approach these sequences methodically. The first step is to gather objective information about the move instead of relying on your initial impression. Here's how to break down and assess moves that feel too big:

Take Measurements

You can use the Starfish technique to measure your reach between big moves. Starfishing is when you climb up to the desired hold or holds you want to reach and use your body as a measuring stick.

When you’re on the destination hold, see just how far the other hand and footholds are. Do you have slack in your arms or legs? How far do you have to lock-off your low arm to be able to reach the next hold?

The more you can collect an objective group of facts about the distances of the holds, the more empowered you’ll be to troubleshoot and send. You might also find out that the move truly is too big for you, and that you need to find alternative beta. Either way, you will know more after starfishing than you did before.

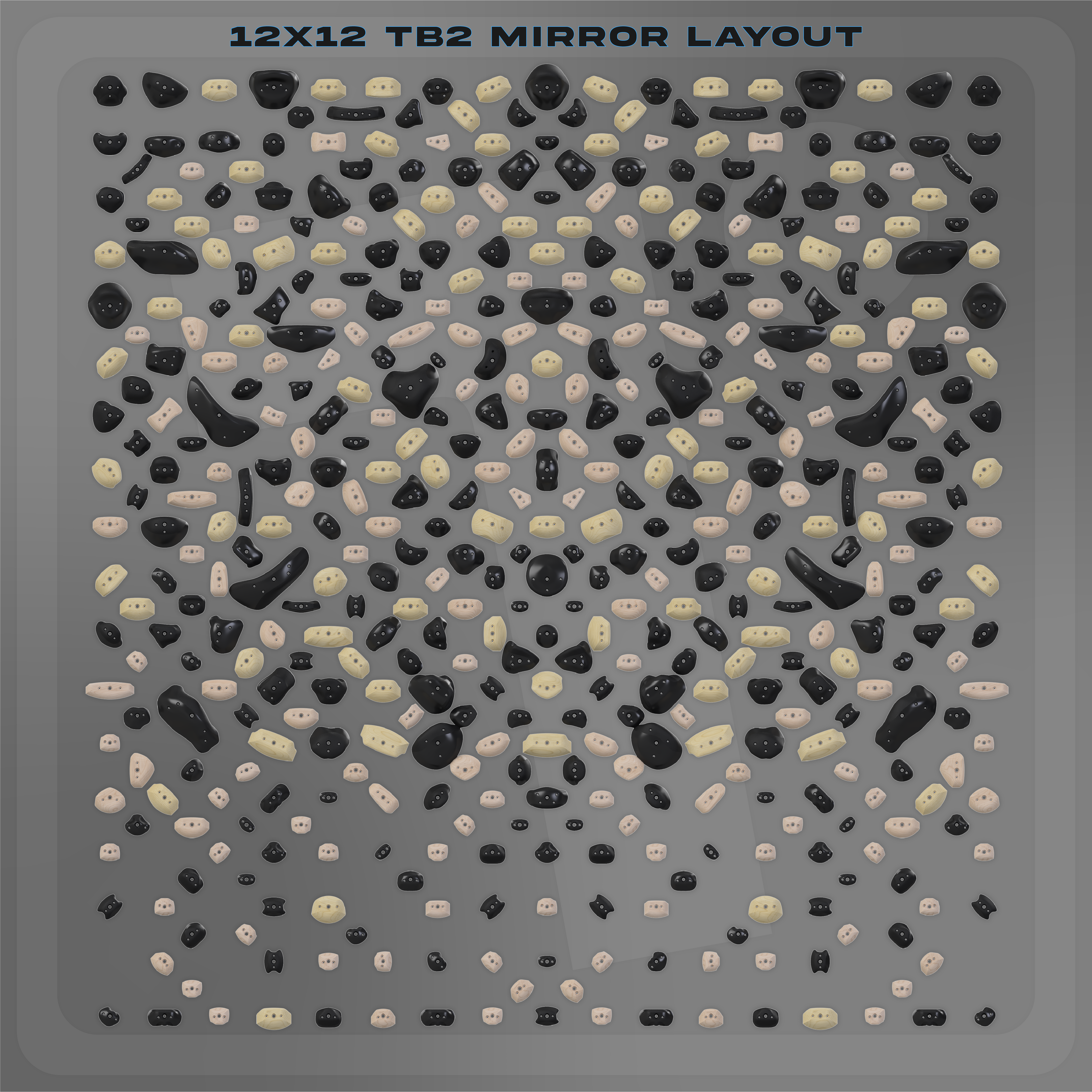

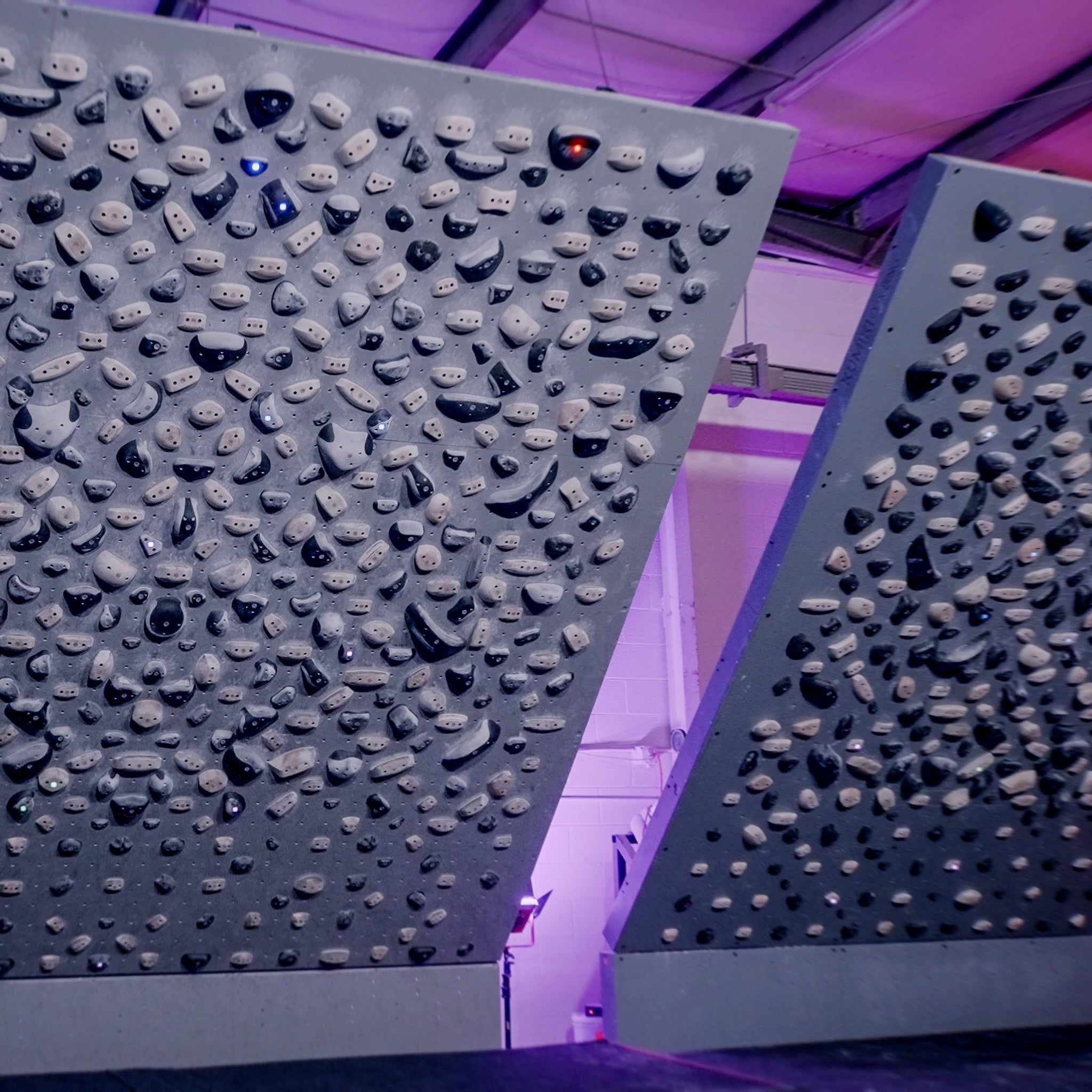

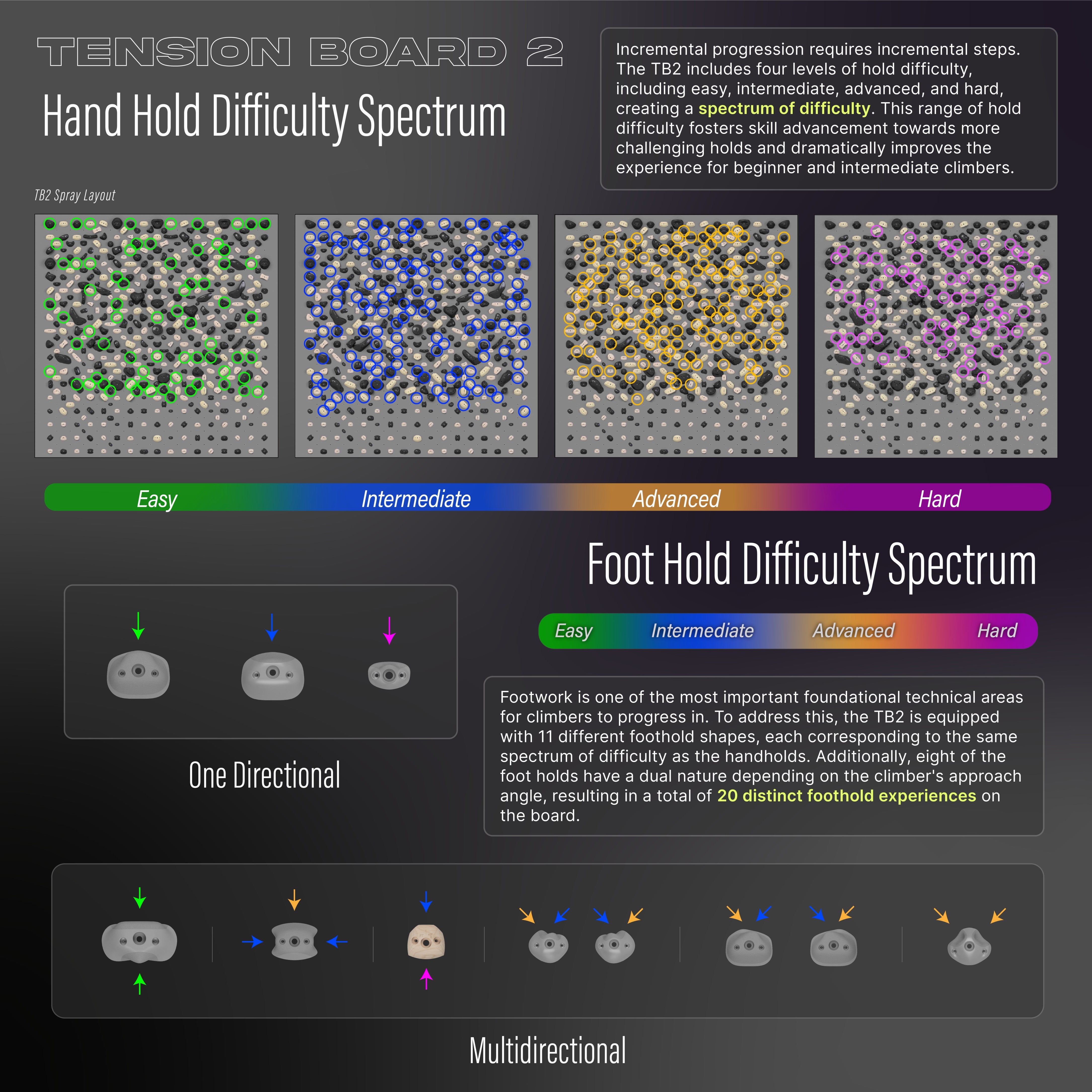

Note, if you’re projecting on a board, say, the Tension Board 2, you can assess the distance between holds with rows and columns for additional measurements.

Starfish, or if you’re on a board, learn how many columns and rows you can reach.

Set Your Own Problems on an LED Climbing Board

Setting your own problems lets you mimic exactly what is hard about big reaches. Setting your own climbs is one of the best ways to learn the nuances around movement and technique.

How do smaller footholds change the way the big move feels? What if you make the holds larger, but less incut? What happens when you make a move bigger by moving the hold wider, rather than further up the wall? How does wall steepness change your experience with big moves?

Most people go through their climbing career never setting climbs for themselves. Fortunately, it’s easier now than ever to explore that option with spray walls or boards.

Repeat, then Iterate

When you find a move or problem that feels challenging for you, continue to repeat it throughout time. As it becomes more comfortable, make small adjustments: Use feet in slightly worse places, use worse hands or hands that are wider or further apart than in the original problem.

Rather than reinventing the wheel every time you need to challenge your ability to do big moves, you can make small changes to the handful of problems that have worked well in the past. This will allow you to keep getting as much value out of those movements as possible.

Truth 4: You’ll Have to Search to Find the Right Beta

The better you get at climbing, the more complex it becomes. Finding and optimizing your beta is something that will persist through every grade, and it’s something you can continue to improve even decades into climbing.

People tend to be fairly binary with beta-finding abilities. Some people don’t struggle at all with the process of problem-solving on a boulder, and some people climb multiple grades lower than their capabilities if beta has not been dispensed to them.

Beta-Finding Strategies

Here's my advice when it comes to the process of beta-finding:

Climb All Styles

Different hold types, wall angles, rock types, and general climbing styles tend to have unique themes about them. While you don’t have to climb on a broad range of styles to become proficient in problem-solving, it will do a lot of the heavy lifting for you if you do. The more knowledge you have about various climbing styles, the higher your ability for problem-solving.

Watch Other People

Struggle on your own first, and then search for the differences between what you tried on your own, versus what worked for everyone else. Can you figure out why you choose your way? Is this a style you are over-reliant on? Were you just not aware that the other way existed? How can you spot that other beta next time?

If you don’t have other people around you to reference for beta, finding video online is the next best thing. While this is easier to do outdoors, some gyms and most commercial boards have video databases for their climbs that you can use to help level up your problem solving.

Truth 5: The Holds Face the Wrong Way

Where big moves feel like a measurable and objective problem, having the holds feel like they’re facing the wrong way is the exact opposite. Feeling like the holds are facing the wrong way is hard to describe and hard to measure—but you know it when you see it, and feel it.

Each person will feel differently about which hand holds and foothold directions feel wrong or right. Due to the subjective nature of it, this truth’s main tenant is to pay attention to your own self-talk when you encounter one of these moves or boulders.

Self-Analysis Questions

Test yourself by asking, ”What is it that makes me say this hold is facing the wrong way?” Is it too much of an undercling? Is the culprit usually a gaston? Is it because you have to claw at the foothold rather than push into it?

A good way to speed run this diagnostic test is to walk through a gym or, better yet, swipe through problems on a board, read the beta, and notice when you find yourself thinking things like:

- “That looks weird.”

- “The holds look okay, but they’re facing the wrong direction.”

- “Ew.”

If a hold seems like it’s facing the wrong way, it’s because you have an idea in your head of what the “right way” should be. Your goal here is to expand your idea of what “right” is. Rocks weren’t built for humans. They are physical puzzles that we have to learn to navigate. There is no right or wrong. Some methods might feel less ideal than we’d like, but that’s climbing.

Find what your “wrong” is, and seek it out. Track down problems or sequences that you can work on and get repetitions on until it starts to feel less foreign.

Truth 6: The Feet Aren’t Where You Want Them

When it comes to the obstacle of feet not being where we want them, there are two aspects of climbing that have skewed our way of thinking:

- Climbing outside: Many rock types are heavily textured. This means that even if there isn’t a foot exactly where you want it, you’re often given an array of sub-optimal options to choose from. You’ll probably still end up on that one foot that isn’t exactly where you want it, but we tend to complain about it less when we’re given the illusion of choice.

- Climbing inside is made to be accessible: In an effort to make climbs more enjoyable and inclusive, routesetters include a mix of footholds in fairly ideal places in order for climbs to flow well for as many body types as possible. As wonderful as this is to climb on, it can lead to feeling like anything less than full foothold accommodation is lazy routesetting or just plain bad climbing.

Do you regularly say to yourself, “I wish there was a foothold right here?” Saying it once is fine. Verbal processing is a valuable part of the problem-solving process for many people. However, if you find yourself constantly saying that feet are in the wrong place, then you’re wasting energy thinking about something that you can’t change. Also, if this is something you say regularly, the problem likely lies more with you than with the climbs themselves.

Our hips are capable of an incredible range of motion and strength. Start putting them to use.

Here’s how to address bad or missing footholds:

- Find the specific situations that make you feel like the feet are in the wrong place.

- Look for patterns among these situations. It’s most likely that there are one or two common situations that are making up the majority of your complaints.

- Recreate these situations on the wall so that you can get practice them. You can set moves yourself or find problems that replicate this.

- If you’re doing this on a board, curate a list of problems that you can repeat in the hard–but-doable” difficulty range, as well as some short-term projects that take 3-5 sessions to complete.

- As you feel more competent with this style, iterate on it. Continue to make small changes to the moves to make them harder. Try to dial in what exactly it is that’s challenging about this type of move. Sometimes all it takes is using a foot that’s one t-nut left or right to make a move feel nearly impossible again.

The more capable you are with your legs, the less stress it’s putting through your fingers. Developing finger strength is a long slow process. The more you can level up your climbing in ways that support your fingers indirectly, the better.

Truth 7: The Positions Are Challenging

I intentionally put "self-belief" at the top of this list because I feel it plays a significant role in all of the truths and obstacles listed.

Without belief, the threshold for what makes a hold feel too bad or a move feel too big becomes significantly lower, because self-doubt can cause us to lose touch of reality.

In a similar vein, I put "position" towards the end of the list because the points above feed into what makes positions a challenge. Also, it is arguably the most challenging one to describe or measure so having the other ones come first will hopefully make it a little easier to understand.

Understanding Positioning

One of the biggest challenges with understanding positioning is that it’s constantly changing based on the hold’s orientation, depth, degree of incut, distance from one another, texture, the angle of the wall, and your own physical size, strength, and state of fatigue at that part of the problem or route.

To put it as simply as I can, positioning is putting your body in the most advantageous place in space to be able to do a move.

Learning From Bad Positioning

Maybe the easiest way to understand the power of good positioning is to look at how punishing bad positioning can be. Think about whenever you watch beginners trying to use a side pull for the first time. They don’t know how to get to the side of the hold and lay back the move. Instead, they pull straight out on the side pull the same way they would with a down pull, which results in them turning the rock climb into a wrestling match.

Basic Position Fundamentals

When we learn basic positions like laying back a side pull, staying underneath a sloper, or letting our hips come out away from the wall when we are smearing, it grants us access to entirely new styles of climbing. While positioning starts to feel more vague after these early lessons, it remains just as powerful of an influence on our climbing.

Recommendations for Improvement

If you want to improve your positioning, here are a few recommendations:

As odd as this might seem, beginning with one-leg climbing can be a fantastic way to learn about positioning. The fewer points you have on the wall, the easier it is to find balance. Climbing full problems with only one leg and then repeating the with the other is a useful tool for positioning practice.

Try moderately difficult moves low to the ground multiple times only changing where your body’s start position is. Staying low to the ground allows you to easily repeat the move with some level of consistency compared to when you have to climb halfway up a wall every time.

Initially try the move with a starting position that feels most natural, and then continue to repeat the move while being slightly higher, lower, left, or right. Once you’ve tried those changes, you can play with being closer or further from the wall as well as being more square or twisted for your start position. Try a mix of different positions and pay attention to how those changes make the move feel.

As you feel more comfortable with finding good positions for individual moves, move to full problems that are easier and try to find good positions on the fly.

Watch how other climbers move in and out of positions and attempt to mimic their methods. Everyone is different, but success leaves clues. Maybe the way the stronger climber moves looks harder, but their position end up making the problem easier.

As you improve at this, you might find that some of your problems with holds facing the wrong way, feeling hard to use, or feeling too far begin to feel less severe.

Common Position Challenges

Keep in mind, knowing what position to be in is only half the battle. Keep in mind:

- Being fatigued halfway through a boulder will make it harder to get into the perfect position for the crux move.

- Any performance anxiety you have around wanting to send might cause you to lose patience and rush your positioning.

- Being able to strike a balance between high-level body tension and subtle body positioning will prove to be more of a challenge than you anticipated. The two often feel at odds with each other.

- If you’re bringing a high level of intention to your practice, you’ll likely find that you get so mentally fatigued towards the end of limit climbs that you struggle to execute good positions.

Position and belief are the two items on this list that can have the greatest leverage over your climbing. Stay patient with improving them, and you’ll continue to see benefits year after year.

Truth 8: It’s Hard to Link That Many Hard Moves in a Row

(To clarify, this section is talking about linking together moves on a boulder problem or in the crux of a route. Having the fitness, tactics, and mental fortitude for linking entire routes goes beyond the scope of this article.)

As fun as it is to do individual hard moves, eventually you need to start linking them together if you’re going to send climbs. While it’s pretty easy to identify when you have a problem linking all of the moves together, understanding why it’s happening takes a little more thought.

We naturally want to blame endurance or power endurance, but there are a handful of other items to check off of the list first before you have to slog through some endurance circuits.

Questions to Ask Before Blaming Endurance

- Do you believe that you can link all of the moves together?

- Have you used good tactics like rehearsing all of the moves and doing overlapping links on the problem ahead of time?

- Are you fresh enough in the session to have a good shot at this?

- Are you able to modulate your effort level by relaxing through the easy moves and trying hard for the most difficult moves?

If you are good about stacking all of the odds in your favor, and can regularly do all of the moves on climbs in isolation, but struggle to link them then it’s worth investing some time into your fitness.

For most climbers, a great place to start is with repeat circuits. For most climbers, their gym sessions look like: warm-up (hopefully), try hard until they are kind of tired, maybe do some fun looking easier climbs until they are tired, and then go home. If that’s you, I have a simple suggestion that can improve the quality of your session as well as your ability to link more hard moves.

While there are infinite ways to do circuit workouts, this is what I recommend as a starting point for most people.

Circuit Training Blueprint

Schedule- Frequency: Once per week

- When: After warm-up, while fresh

- Brief warm-up on hard problems

- Select 4-8 problems (-2/-3 V-grades below project)

- Rest: 3 minutes between attempts

- 3 attempts per problem

- Target: 50% success rate

- Total session time: Stop before exhaustion

- IF success rate < 50%: Add easier problems to reach 4 minimum

- IF completing all 8 problems: Replace easier problems with harder ones

- Build climbing fitness through consistent, high-quality volume

The terrain you choose for your circuit can either be varied, specific to your current goals, or a mix of varied and specific. I prefer the latter.

Using Standardized LED Boards for Circuit Training

While commercial sets will offer a more complex variety for circuits, they have a limited lifespan. This means that if you always use commercial sets, you’ll regularly have to find new problems for your circuit. For this reason, boards are fantastic tools for doing repeats. I believe boards are especially useful circuiting tools for sport climbers or predominantly outdoor climbers because they likely won’t spend enough regular time on the commercial bouldering sets to develop a worthwhile circuit.

If you are using a board for your circuit, I recommend making several lists based on climbing style or difficulty. Also, if you have access to a mirrored board, this will allow you to do circuits while only needing half as many problems. This can be a fantastic jumping-in point for someone who feels overwhelmed by the idea of finding eight moderately hard problems to attempt.

If the idea of circuits feels too structured for you, one other method that can be helpful for training to improve at linking more moves together is to pick projects that are more sustained and less cruxy in nature. If you always choose 2-5 move problems to work on, occasionally pick something closer to the 6-10 move range. This will give you more time to practice linking relatively hard moves together while moderately fatigued.

As for off-the-wall training: While you can work on your ability to more hard moves together by focusing on off-the-wall methods like hangboard repeaters or similar modalities, at the time of this writing, I only recommend that for the most time-poor climbers. Being able to remain mentally and technically composed while fatigued is the mark of an expert climber. It’s for that reason that I believe that improving your climbing fitness with climbing worth doing when time allows.

Final Thoughts

Throughout this article, we've explored eight fundamental truths about climbing harder - from bad holds to linking moves. Each obstacle presents its own unique challenge, but they all share a common thread: the solution lies in methodical practice, self-awareness, and patience.

Rather than seeing these challenges as roadblocks, view them as signposts guiding your progression. Whether you're struggling with small holds, awkward positions, or linking sequences together, remember that these obstacles aren't just challenges to overcome - they're the very elements that make climbing an endlessly engaging pursuit.

As you continue your climbing, focus on identifying which of these truths resonates most with your current challenges. Start there, implement the strategies we've discussed, and trust in the process. The path to climbing harder isn't about eliminating these obstacles - it's about developing the skills, strength, and mindset to navigate them with increasing sophistication.